For those of us experiencing the world in fat bodies, we inherently understand the reality of fatphobia and weight stigma. Recent research being conducted on fatphobia, weight stigma, weight bias and weight-based discrimination may offer critical data to support qualitative and first-hand accounts, and, ultimately, create systemic change.

This research is bearing out what we already know to be true: the world treats fat people poorly on an interpersonal level and a systemic level. Healthcare providers, specifically those who work within the weight loss sector, have the highest rates of negative attitudes towards fat people. These can include: believing that higher-weight patients are lazy, don’t care about their health, are unintelligent, are unhygienic and more. Doctors spend less time with their fat patients. Children who grow up in larger bodies are subjected to high levels of weight-based bullying. Fat people are less likely to be hired and make less than their thin counterparts. The list goes on and on.

The constant and socially-accepted microaggressions that fat people experience don’t just result in emotional upset. Consistently experiencing discrimination makes our stress levels rise, activating our fight or flight response, altering the body to push out a hormone called cortisol. This state of chronic stress results in numerous physical health consequences, including elevated blood pressure. Stigma has a marked impact on our physical health.

How Weight Stigma Bias Impacts Mental Health

For some reason, some people need to know that something might impact our physical health to consider it valid. In my opinion though, how something makes us feel—otherwise known as the mental health impact that something has on us—is just as important as any physical ailment.

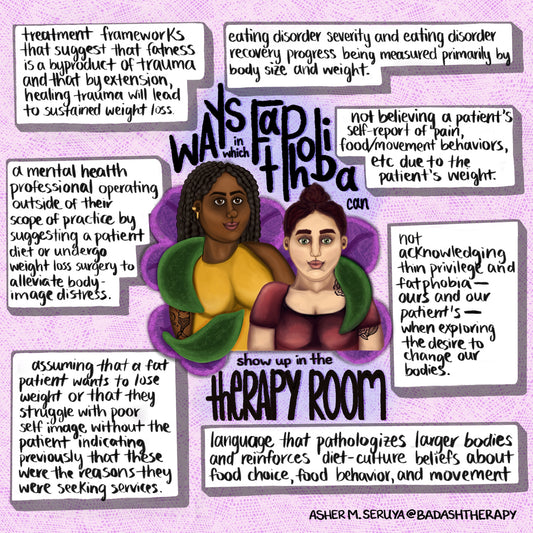

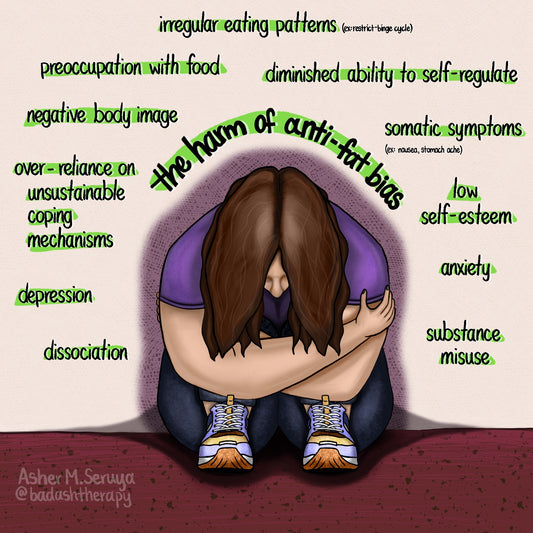

The mental health impacts of weight stigma are vast, and they may change or be more likely based on trauma history and other personal factors. Here is what some of the research is telling us though:

- Struggles with depression and body image were found to be higher among people seeking intentional weight loss, bariatric surgery and binge eating disorder.

- Even when potentially confounding factors were controlled for (BMI, race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc), stigma-induced stress persisted. This stress was shown to contribute to higher rates of substance abuse disorders and anxiety and mood disorders.

- Internalized weight bias was associated with increased body image concerns, dissociation and food preoccupation (Note: the research will often refer to feelings of “food addiction.” To date, we do not have rigorous research to suggest that food is an addictive substance. That being said, the feeling of being addicted to food is extremely valid, especially because our culture normalizes restriction and deprivation. Rather than use the term food addiction, I use the term food preoccupation.)

- Over half of the people who experienced weight stigma also qualified as having at least one psychiatric disorder. As weight status increased, so did psychiatric disorders. Those with higher levels of internalized weight stigma were more likely to experience mental health disturbances. More research is needed to explore causal relationships and potential confounding variables.

- Other potential negative mental health consequences included emotion regulation struggles, negative affect, somatic symptoms and maladaptive coping. Examples of maladaptive coping include binge eating and other eating disorder behaviors, engaging in risk-taking behavior and procrastination. (Note: maladaptive coping is still coping. These are coping mechanisms that we may lean on because they are familiar or feel easy and effective in the short term. That being said, there is no such thing as a “bad” coping mechanism. There are ones that are more sustainable than others, and ones that might not be right for you or should be used sparingly; but they are never bad.)

- Perceived weight-based discrimination was associated with low self-esteem, poor psychosocial functioning, binge eating and psychological distress. Studies also suggested that percieved weight-based discrimination has just as much of an impact as true and intentional weight-based discrimination. This highlights the fact that even the fear of experiencing fatphobia is in and of itself a stressor, whether or not weight stigma is actually occurring. It also illustrates the fact that weight stigma harms us all. Whether or not we are actually fat, even the threat of fatness can negatively impact our mental health. It is one of the things that we fear most, whether or not we are already fat.

- Internalized weight bias was found to be a significant and independent risk factor for poor self-esteem, over and above BMI. This highlights the fact that how we conceptualize our bodies and the degree to which we internalize the fatphobic messaging that saturates our world is a bigger predictor of low self-esteem, no matter our size.

Prevention: Looking Ahead

We might feel frustrated or angry at the existence and prevalence of weight stigma. We are absolutely entitled to that anger and pain. However, such research, although painful to read, is essential in beginning to alleviate and prevent discrimination and weight stigma. In other words, the research that illustrates the intricacies of weight bias also gives us information that we can use to teach weight-bias prevention.

Some strategies include: actively challenging fatphobia rather than continuing to blame individuals for their size, moving away from the model of shame and integrating a weight-inclusive approach to wellbeing.

Sources

Associations Between Perceived Weight Discrimination and the Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in the General Population, Hatzenbuehler (2009)

Obesity Stigma: Important Considerations for Public Health, Puhl and Heuer (2010)

Investigating the Relationship between weight-related self-stigma and mental health for overweight/obese children in Hong Kong, Chang (2019)

Weight Bias Internalization and Health, Pearl and Puhl (2018)

How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health, AJ Tomiyama (2018)

Originally posted on Center for Discovery’s blog